The Earliest Days

When Toronto was incorporated as a city in 1834, it had a long way to go towards becoming the metropolis of today; it’s population at the time was barely 10,000, or less than half the current population of Owen Sound. Though Toronto was already a significant commercial centre, the only transportation the city could boast were stagecoaches to and from such communities as Kingston, Niagara, Barrie and London. Local transportation did not exist, as horses, feet, and private carriages were enough to meet the transportation needs of the city’s residents.

In 1849, however, with the city’s population having grown to 21,000, a Yonge Street cabinet maker and undertaker named Burt Williams saw a market to be exploited. Using his skills, he built a four smaller, more comfortable stagecoaches which he called omnibuses. These vehicles, which could hold six passengers, began running along King Street and Yonge Street, starting at the St. Lawrence Market and ending at the village of Yorkville in front of the Red Lion Hotel. The ride took ten minutes to complete and cost a sixpense. The service was immediately popular and, within a year Williams expanded his omnibuses to handle ten passengers. More buses were added to the fleet within a few years, so that service operated every few minutes.

The Rise of the Toronto Street Railway Company

The popularity of Williams’ service had already demonstrated to city council and various business interests the viability of public transit in the city. This would prove to be his undoing. In 1861, Alex Easton, a Philadelphia native came to Toronto to help set up a conglomerate of local business owners to build a street railway in the city. Having travelled to New York, Philadelphia and Boston, he was an ardent promoter of street railways and wanted to promote his new, horse-drawn ‘Haddon Car’. On May 29, City Council granted this group, now known as the Toronto Street Railway Company (TSR) a 30 year franchise. Easton, now president of the company, had his men start work on laying down tracks, and Toronto’s first streetcar route started operation on September 11, 1861.

The first route duplicated Williams’ omnibus service, following tracks from St. Lawrence market laid down along King and Yonge to the Yorkville Town Hall. The second route started operation on December 2, 1861, running along Queen Street west from Yonge Street to the mental hospital at the foot of what was then known as Dundas Street (today’s Ossington Avenue). The streetcars were all pulled by horses, and the car barn and horse stalls were located in Yorkville.

Williams tried to compete with the new service, even changing the gauge of his wheels to make use of the new tracks, but the writing was on the wall. The Toronto Street Railway had deeper pockets, bigger cars and, most importantly, the support of city council. Williams would sell his assets in 1862 and return to his undertaking business.

It was at this time that the current non-standard TTC track gauge was established. There is some confusion over why the odd 4ft 10-7/8in width was chosen for the horse car running rails. Historians working for the Toronto Transit Commission suggest that this was established to assure city councillors that steam railways would never use the street tracks to get around. Other historians point out that the gauge was the width of an English Wagon, and so was useful in order to improve the handling not only of the streetcars, but of other wagons using the street. Toronto was not far removed from its days when it was known as ‘Muddy York’. Until the streets were paved, many private wagons made use of the streetcar tracks in order to get around Toronto’s dirt roads.

Steps Towards Electrification

In the 1870s and 1880s, electricity transformed from an experimental curiosity into something practical that could light cities and moves vehicles about. The 1880s found John Joseph Wright, an English immigrant, experimenting with electricity in a small shop near Yonge and King, and selling light bulbs and the electricity to light them to various shops and factories. By 1883, Wright had set up the Toronto Electric Light Company. At that time, he was approached by senior staff at the Toronto Industrial Exhibition to build an electric railway for their fair, inspired by a similar attraction that had been unveiled in Chicago.

Wright worked with a Belgian-American immigrant and electrical expert Charles Van Depoele to get an experimental line working in time for the 1883 Exhibition, but the line did not perform satisfactorily. They tried again in 1884 and succeeded in building a line from the terminal of the TSR’s King-Exhibition line at Strachan Avenue into the Exhibition itself, a distance of about a mile. Initially using third rail pickup, the two switched to a trolley-pole design in 1885, when the train carried over 50,000 passengers. The experimental electric railway would operate until 1889 before it was abandoned, but city officials had been convinced of the advantages of electric operation, reducing the cost and environmental impacts of horsecar operation.

The First Stab at Public Ownership

As Toronto grew, so too did the ridership of the Toronto Street Railway, from 44000 in 1861 to 55000 in 1891, when the TSR’s 30-year franchise expired. On May 16, 1891, the city sought to take over the system. The attempt did not go as well as planned.

The city first ordered the Toronto Street Railway Company to agree to hand over operations without first establishing the price. In protest, the company ordered all streetcars off the streets. Arbitration cooled tempers and, by the end of May, a price of $1.4 million was agreed to, and public operation began. A few months later, however, the city of Toronto decided that it was too risky to own and operate the street railway. Lured by promises a new consortium of businessmen were making about electrifying the streetcar system, Toronto City Council granted a 30 year franchise to the new Toronto Railway Company. The TRC took over operations on September 1, 1891. The businessmen kept their word, and electric streetcars started running on Church Street on August 16, 1892. The last horse car would gallop up McCaul Street on the DOVERCOURT route on August 31, 1894.

The Other Street Railways of Toronto, 1877-1921

Toronto & Mimico Electric Railway and Light Company (1890-1906)

Chartered November 14, 1890, running from Sunnyside, along the lakeshore of Humber Bay to Humber River. Extended to Mimico in 1893, Long Branch in 1894 and Port Credit in 1905. Acquired by Toronto & York Radial Railway in 1906, and then by the Toronto Transportation Commission on January 11, 1927.

Toronto & Scarboro Electric Railway, Light & Power Company (1892-1906)

Incorporated August 18, 1892, running from Kingston Road and Queen Street, east along Kingston Road to Blantyre and south on Blantyre to Queen. A branch extended north from Kingston Road via Walter, Lyall and Kimberley to Gerrard. Service was removed from Blantyre in 1897 and extended east on Kingston Road to Hunt Club, with further extensions to Half Way House in 1901, the Scarborough Post Office on 1905 and West Hill in 1906. Lines acquired by Toronto & York Radial Railway in 1906 and then by the Toronto Transportation Commission on January 11, 1927.

Metropolitan Street Railway Company (1877-1906)

Incorporated in 1877, established service on Yonge Street from the Canadian Pacific tracks to Glen Grove Avenue in 1884. Extended to York Mills in 1886, Richmond Hill in 1896, Newmarket in 1899, Jackson’s Point in 1907 and, finally, Sutton in 1909. Acquired by the Toronto & York Radial Railway in 1906. The section within Toronto’s City Limits was assumed by the Toronto Transportation Commission in 1922, while the remainder of the line was bought on January 11, 1927. The section from Richmond Hill to Sutton was abandoned on March 13, 1930, while the remainder of the line between the city limits and Richmond Hill was operated as the North Yonge Railways, under contract by the TTC and the townships of North York, Markham, Vaughan and Richmond Hill until October 10, 1948.

Toronto Suburban Railway Company (1894-1931)

Incorporated February 1894, taking over assets of the City & Suburban Electric Railway Company (incorporated 1891) and the Davenport Street Railway Company (chartered 1891). Operated services on Davenport Road, Dundas Street west of Humberside and Weston Road along with private right-of-way services to Woodbridge and Guelph. Taken over by the Canadian Northern Railway in 1918. All lines within Toronto’s city limits taken over by the TTC on November 15, 1923, with service to Weston taken over by the City of Toronto, the Township of York and the Town of Weston in 1925. Remainder abandoned by 1931.

Information courtesy “Street Railways, Toronto: 1861 to 1930”, compiled by J. William Hood for the Toronto: Maps Project, 1999.

William Mackenzie Takes Over

The Toronto Railway Company’s president and owner was William Mackenzie, a railroad mogul who had founded the Canadian Northern. In the TRC’s first years, Mackenzie introduced a number of innovations, and his leadership proved popular with the public. The new company maintained a five cent fare, introduced free transfers and reduced fares for children and students. Fares continued to be collected by a ticket collector moving up and down the cars with a ‘coffee-pot’ farebox, however, as attempts to establish the pay-as-you-enter system that we know today were dropped in December 1910 due to rider objections.

As the TRC neared the end of its franchise, however, its willingness to maintain a top-quality system started to flag. Mackenzie’s national railway interests were running into hard times, and his attempts to construct his own transcontinental railway broke him. There was certainly less money to invest in his Toronto operations. After the turn of the century, Toronto annexed vast tracts of land in the villages surrounding the city, and ordered the TRC to service the new areas. With the TRC uncertain whether its franchise would be renewed in ten years, they refused, claiming that their original franchise covered only the area within the city’s 1894 boundaries and they were not obliged to service the newly annexed lands. A court sided with their argument.

Ironically, the TRC’s hard-nosed position probably ensured that the City of Toronto would not renew their franchise in 1921. However, the expiration of the franchise was still ten years away, and the city still had to find some way to service the newly annexed areas, whose residents were clamouring for service. With the TRC still refusing to run streetcars into the new areas, the City of Toronto decided to provide the service themselves, and the Toronto Civic Railways were formed, constructing new lines along the Danforth, east Gerrard, Bloor West, St. Clair and Lansdowne Avenues. Knowing that the two systems would be combined under municipal ownership, the TCR built its tracks to the TRC’s 4ft 10-7/8in gauge.

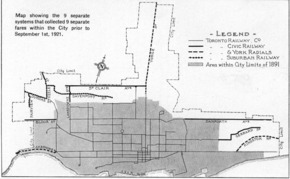

Although the new areas received their service through the city’s actions, the public transit situation had became very complicated during the 1910s. With its annexations of West Toronto and North Toronto, the city inherited other streetcar systems, like the Toronto and York Radial Railway and the Toronto Suburban Railway (see inset). With the TCR split into four separate systems, each collecting their own fares and offering no transfers between them, a Toronto traveller paid anywhere from 2 cents to 15 cents to travel across the city. The City of Toronto resolved that, once the TRC’s franchise ran out, that it would merge all of the networks into a single transit system. On January 1, 1920, voters approved municipal operation of all streetcar service in the city and, on September 1, 1921, the city owned Toronto Transportation Commission was born.

The TTC Through Boom, Bust and War

The 1920s was a period of great activity within Toronto. Not only was there considerable work in uniting the operations of the Toronto Railway Company and the Toronto Civic Railways, but the TTC had also inherited from the TRC an aging system which had been left to deteriorate by its disinterested owners on the eve of the end of their franchise. A lot of work went in to replacing miles of track, and a lot of money was spent on purchasing new equipment, including 575 steel-bodied Peter Witt streetcars. The TTC entered into negotiations to purchase the operations of the Toronto Suburban Railways and the various radial railways and, by 1927, all streetcars in Toronto were being run by the TTC.

The boom times ended with the stock market crash in 1929, but the TTC weathered the 20 percent ridership loss and continued to make improvements. In 1938, the TTC invested in the new Presidents’ Conference Committee car, designed by a committee of American transit company presidents to wrest back riders from the emerging private automobile. The PCC was a wild success, but the Second World War was more responsible for the resurgence in public transit ridership. Buses were bought, and plans were drawn up for a new subway.

In 1942, the TTC proposed the construction of underground streetcar lines on Queen and Yonge, but it was only in 1946 that voters approved the construction of a full fledged subway underneath Yonge Street, as well as a streetcar subway beneath Queen. Construction began on the Yonge line in 1949.

Metropolitan Toronto and the Car Change the Picture

In the early 1950s, Toronto and its suburbs had to contend with sprawling development held back after two decades of depression and war. In order to answer the problem of sharing infrastructure funding and distribution, the Province of Ontario took the step of collecting Toronto and its twelve suburbs under the auspices of the Municipality of Metropolitan Toronto, which took power on January 1, 1954. The Toronto Transportation Commission was brought under the jurisdiction of Metro, and at the same time was renamed the Toronto Transit Commission. The new agency now had responsibility of an area several times larger than its predecessor.

The province continued modifying the Metro system over the years. In 1967 the seven smallest suburbs were amalgamated into larger adjacent municipalities, and in 1998 the federated system was abolished and the Metro area became a unified City of Toronto. These changes did not greatly affect the TTC, however, since it was a Metro responsibility.

Three months after its reorganization, the TTC opened Canada’s first subway. Running down Yonge Street from Eglinton Avenue to Union Station, it was an overnight success, and plans were drawn up for expansions. Although the first subway was paid for almost completely from the farebox, the TTC’s ability to pay for extensions to that subway flagged as bus service quadrupled, and the TTC was called upon to establish unprofitable service to the suburbs. Development was outpacing the TTC’s ability to service it, and the automobile was turning out to be the average citizen’s first choice for his or her transportation needs. Metro Toronto had to step in with additional capital subsidies, and then the Province followed suit, until the TTC’s entire capital budget ended up paid for exclusively by taxpayers. Toronto did get the subway expansion it needed however.

The TTC continued to make an operating profit until 1972 when, under political pressure from the suburban majority on council, the TTC eliminated its fare zone system which previously obliged suburban residents to pay an additional fare. By the late 1980s, the annual cost of keeping the TTC afloat was now up to a quarter of a billion dollars of taxpayers’ money, although at 32% of all revenues, this was the lowest subsidy required of any city in North America.

As subway expansion continued, so too did the shrinking of Toronto’s streetcar network. The conventional wisdom at the time had streetcars as a leftover from a previous era. It was only in the 1970s, in the era of protest against the Spadina Expressway and car-oriented development, that local citizens convinced the TTC that streetcars meant better service. The TTC abandoned its streetcar abandonment policy in 1972, and the Rogers Road streetcar was the last streetcar to fall under that policy. The TTC used the streetcars released from Rogers Road to maintain the fleet until it could find a builder for a new generation of railed vehicles.

Decline, Fall and Rise

In the 1970s and the 1980s, the Toronto Transit Commission was seen worldwide as a ‘transportation showcase’. From 1979 until 1990, it won awards after awards for safety and design. Unfortunately, in the 1990s, it fell upon hard times. Political foot-dragging slowed subway development to a crawl, and budget cuts, the recession, and the inability to service the rapidly growing areas outside of Metro Toronto cut ridership by almost 20 percent from an all-time high of 460 million. The lowest point came when the first fatal subway train accident in the subway’s 40 year history occurred in August 1995, between Dupont and St. Clair West Stations, a combination of driver error, inadequate maintenance and a safety equipment design flaw.

The TTC has begun to pull itself out of its bad times, however. Under the management of General Manager David Gunn, imported from the United States where he received good reviews as manager of New York and Philadelphia’s systems, spending on maintenance increased dramatically. Funds are still very tight — the TTC’s level of subsidy required is 25%, the lowest of any local transit agency on the continent — but the TTC is working on increasing service. On July 27, 1997, service began on the new Spadina Streetcar, restoring service to that street 31 years after its abandonment and the TTC continues to work on other improvements including the Sheppard Subway and the Queens Quay streetcar link.

Today, in 2009, ridership has returned to its record levels of the late 1980s, and service is improving. Although there are still concerns about the future, particularly with Toronto’s budget stress, the system’s funding is stable for now, and the provincial government has stepped forward to fund an ambitious project to build advanced light rail lines on or, in some cases, beneath Eglinton, Sheppard and Finch Avenues.

The TTC continues to provide a vital service to the citizens of the City of Toronto, and will likely continue to do so for the foreseeable future.

Where Do I Go From Here

- Click here for our history of the Toronto subway

- Click here for our history of Toronto’s streetcar routes

- Click here for our history of Toronto’s bus network, particularly 82 Rosedale

- Click here for our history of GO Transit

- Click here for our history of TTC Fares

References

- Bromley, John F., TTC ‘28, The Upper Canada Railway Society, Toronto (Ontario), 1968.

- Bromley, John F., and Jack May Fifty Years of Progressive Transit, Electric Railroaders’ Association, New York (New York), 1973.

- Filey, Mike, Not a One-Horse Town: 125 Years of Toronto and its Streetcars, Maps Project handbooks, Toronto (Ontario), 1999.

- Hood, J. William, Street Railways - Toronto: 1861 to 1930, Maps Project, Toronto (Ontario), 1999.

- Hood, J. William, The Toronto Civic Railways: An Illustrated History, The Upper Canada Railway Society, Toronto (Ontario), 1986.

- Pursley, Louis H., Street Railways of Toronto 1861-1921, Ira Swett, INTERURBANS, Los Angeles (California), 1958.

Thanks to Mark Brader for correcting this web page and offering additional information.